Epidemics in Wroclaw: Plagues took away every third inhabitant of the city

Plagues occurred every 10–15 years. Physicians had a high position during epidemics. Barcelona paid ransom for two abducted doctors. Imagine that someone abducts Wroclaw’s expert in infectious diseases Professor Krzysztof Simon today and the city has to pay ransom for his release, says Maciej Łagiewski, the director of the City Museum of Wroclaw.

When the first lockdown was announced in the spring of 2020, the streets of Wroclaw became completely empty. The sight of the dead-looking city inhabited by several hundred thousand people was disheartening. In accounts of epidemics in Wroclaw in the 16th or 17th century, we can also read about closed inns and schools, empty churches or the prohibition to organise dances.

Such analogies can actually be found. However, old descriptions of cities subdued by an epidemic are more dramatic. They refer to funeral processions moving throughout the city. Carts full of dead bodies incensed with suffocating smoke dragged across the streets. Burning corpses or incensing them with wormwood or juniper was believed to be a recipe for the bubonic plague. In addition, the ringing of church bells could be heard in every part of the city.

How often was Wroclaw haunted by plagues?

The plagues of medieval and modern times affected mainly such big cities as Wroclaw, which was situated on an important merchant and military route.

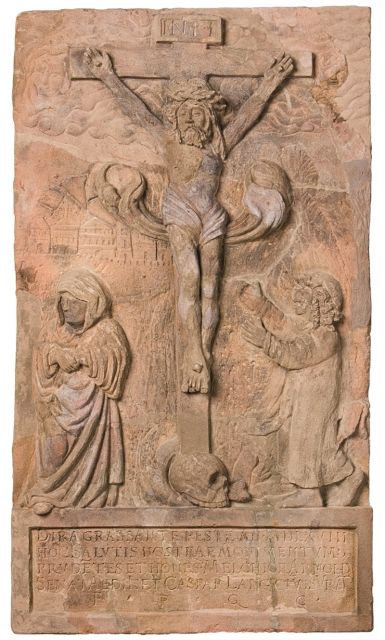

Wroclaw and Silesia were affected by epidemics, too. In the Royal Palace in the City Museum of Wroclaw, we can see a plaque that commemorates victims of the plague epidemic in 1568. It was funded by city councillors Melchior Arnold and Caspar Lang. This object resembles a collective epitaph or tombstone – a kind of secular monument that was exceptional in those times. The plaque was placed on the façade of the building at ul. Ruska. It refers to nearly 9,000 dead people. At that time, Wroclaw had 30,000 inhabitants. This means that almost one third of them died.

Keeping the proportions, this would correspond to 250,000–300,000 Wroclaw inhabitants dying from Covid-19 today.

It was one of the bigger epidemics in the history of Wroclaw. It is calculated that the previous one took the lives of 13,000 people, but in the entire territory of Silesia.

Commonly called the Black Death, the plague epidemic was obviously not the only one; other epidemics occurred every 10–15 years with varied effect, but they did not leave such a city for a long time. They were usually caused by wars and migrations of the population. Epidemics of typhus and dysentery accounted for 70% of deaths during wars.

The movements of German and French troops during the Thirty Years’ War led to the epidemic known as the Great Plague of Milan that spread throughout Europe in 1633. At first, it spread throughout Italy (an analogy to modern times!), where it took the lives of around 280,000 people. During that time, 60,000 people died in Milan and almost 50,000 in Venice.

Until today, the following prayer has been sung in churches: ‘From the air, from famine, from fire and from war, save us, Lord’.

The air mentioned in the prayer meant obviously the plague. Apart from the plague, cholera, malaria, smallpox and typhus occurred.

Cholera decimated the Napoleonic army, and victims of cholera, typhus and Spanish flu during World War I were counted in millions.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, Wroclaw was fortified with walls. For this reason, cemeteries were located only beside temples. Only Jewish necropolises were situated outside the walls.

Examples of plague cemeteries established after epidemics were those beside churches of St. Elizabeth, Mary Magdalene and Barbara. On the last of these cemeteries, victims of the plague epidemic were buried in mass graves. Here, we can refer to modern times again. After all, the media showed pictures of coronavirus victims being buried in mass graves in New York and in Mexico.

How did cities protect themselves against epidemics?

In special watchtowers built for troops marching through the city, soldiers had their documents checked and forced to undergo a quarantine.

Such watchtowers were usually erected near gates and bridges. The watchtower stood near Zwierzyniecki Bridge; formerly, this bridge was called the Pass Bridge after entry documents that were issued at this point. Symbolic pavilions near Pomeranian Bridge also refer to former watchtowers.

Who buried the dead and treated the infected?

Attempts to rescue plague victims were made by doctors. There were no respirators and vaccines; instead, doctors drained blood, cut out or burned bumps or served mixtures of powdered mummies, deer horn or pearls.

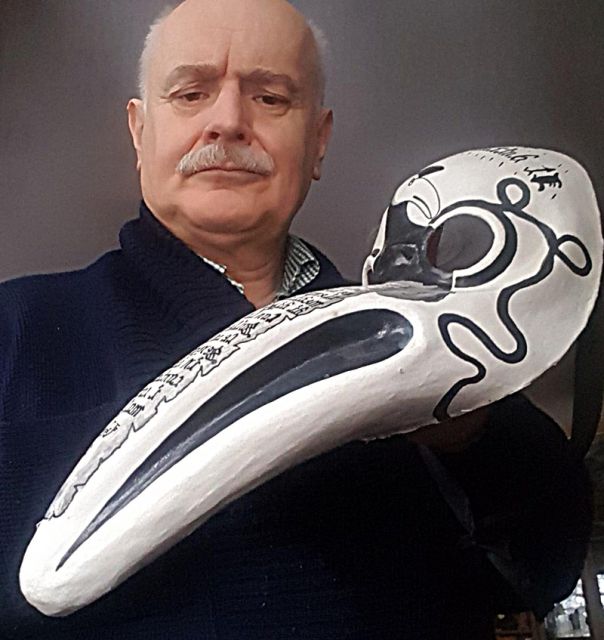

Maciej Łagiewski, director of the City Museum of Wroclaw

Maciej Łagiewski, director of the City Museum of Wroclaw

One of the symbols of the Great Plague of Milan is the characteristic costume worn by physicians in those days. Doctors wore leather hats and special long waxed coats that covered them tightly. They were also distinguished by masks with a characteristic bird-like beak. The mask closed the entire face, and various herbs – juniper, mint, camphor, cloves, roses – that allegedly protected doctors against the polluted air causing illnesses were put into its beak. Apart from that, doctors’ white sticks exposed their profession and the resulting privileges. In the course of time, those who recovered from the plague also began to use this attribute.

The figure of Dottore dressed in this way subsequently appeared in the commedia dell’ arte and became fashionable during the Venice Carnival. The masks that we use today may also become a symbol of the current coronavirus epidemic after years.

Were doctors paid well in those times?

Physicians had a high position during epidemics. Barcelona paid ransom for two abducted doctors. It is as if someone abducted Wroclaw’s expert in infectious diseases Professor Krzysztof Simon today and the city would have to pay ransom for his release.

Once the most famous doctor in Wroclaw was Johann Kraft von Krafftheim. When the plague hit Wroclaw in the 1650, he suspended his private practice and came to the rescue of the epidemic victims. The city even coined a gold medal in his honour and granted a special salary to him. When his fame reached the Habsburgs’ court, Kraft von Krafftheim became the court physician of successive emperors: Ferdinand I, Maximilian II and Rudolph II.

During another epidemic, he engaged in fighting the plague again; this time, upon being infected, he became its victim himself. In 1585, his wife died first and was soon followed by him. His magnificent epitaph is situated in St. Elizabeth’s Church in Wroclaw. He was the example of a doctor who died at the front of fight against an epidemic.

In Boccaccio’s Decameron, the main protagonists are wealthy inhabitants of Florence who took refuge from the plague in the countryside.

In the 16th century, members of the Wroclaw city council fled to Świdnica to escape the plague. During cholera epidemics, Wroclaw inhabitants travelled to Berlin and Dresden, which were less heavily affected by the plague.

Those who had manor houses in the suburbs – already in modern times – took shelter in these mansions. This also reminds us of the present situation. I talked to a university professor who has not left his suburban apartment in fear of going down with Covid-19 for the last few months.

However, the social status and property did not always ensure protection against illness. In 1831, the famous military theoretician Carl Filip Gottlieb von Clausewitz died of cholera in Wroclaw. At that time, the plague killed around 2,000 people in Silesia.

Today there are recurrent theories that coronavirus is a scheme concocted by secret services, companies and states. Who was blamed for epidemics in those days?

Today we know that epidemics were mainly a consequence of sanitary negligences. They affected mainly large crowds of people, many of whom were migrants.

In the past, all kinds of disasters – not only epidemics – were regarded as divine punishment against inhabitants for the ignorance of religious restrictions, the breach of fasts or failure to observe holidays.

This is visible in votive medals. The church and city authorities coined medals commemorating the subsidence of the plague, on which sacred symbols were put in token of gratitude for its disappearance.

Did epidemics have an impact on the city’s economic situation? Did they result in an economic collapse?

The city was always strong enough to recover from such catastrophes. Not only epidemics, but also floods and other disasters.

People believed in the natural rules of history: bad times had to be followed by better times!

The last epidemic in 1963 became a symbol of effective resourcefulness. Wroclaw coped with the smallpox (variola) virus at low casualty rates. And, after all, smallpox was considered to be one of the most contagious diseases in history. The smallpox infection clusters were strictly isolated in the city. However, this was an optimistic experience that, by putting high faith in science and the achievements of medicine, humanity can overcome threats of this kind and things would get better soon.

Tomasz Wysocki